Spamhaus, Spam, and the Shape of Modern Email Filtering

Spam didn’t disappear — it was pushed out of sight. Reputation systems like Spamhaus reshaped email abuse at internet scale, trading noisy volume for quieter, more dangerous attacks. This is the infrastructure that keeps email usable — and the compromises it relies on.

Spam didn’t disappear.

It was pushed out of sight.

For most people, spam filtering feels automatic. Junk doesn’t arrive, inboxes stay usable, and email appears to “just work”. What’s less visible is the infrastructure that makes this possible — and the trade-offs baked into it.

If you haven’t read it yet, my earlier post explains the broader pattern: Why Spam Isn’t Disappearing — It’s Just Changing Shape.

One of the most influential actors in that infrastructure is Spamhaus.

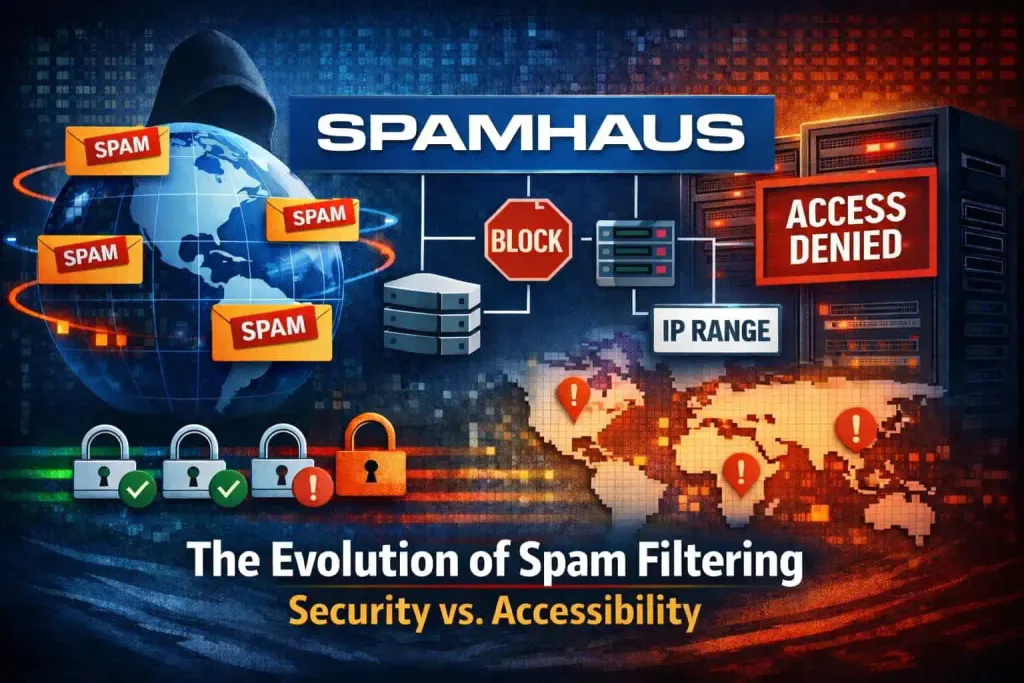

Founded in 1998 by Steve Linford, the Spamhaus Project began as a response to the most visible forms of early email abuse. Over more than two decades, it has grown from a relatively simple blocklist into one of the most widely referenced sources of spam and abuse intelligence on the internet.

Its work dramatically reduced the scale of obvious spam — but it also reshaped spam into something quieter, more targeted, and harder to classify.

That change wasn’t accidental.

It was structural.

What Spamhaus actually does

Spamhaus isn’t an email provider, and it doesn’t read messages.

Its role is reputation.

This is the same kind of “trust-by-design” thinking I wrote about in What Zero-Access Architecture Actually Means (and Why It Matters).

It tracks and publishes intelligence on:

- IP addresses associated with spam, malware, and botnets

- Domains used for phishing, fraud, and abuse

- Hosting infrastructure that consistently enables malicious activity

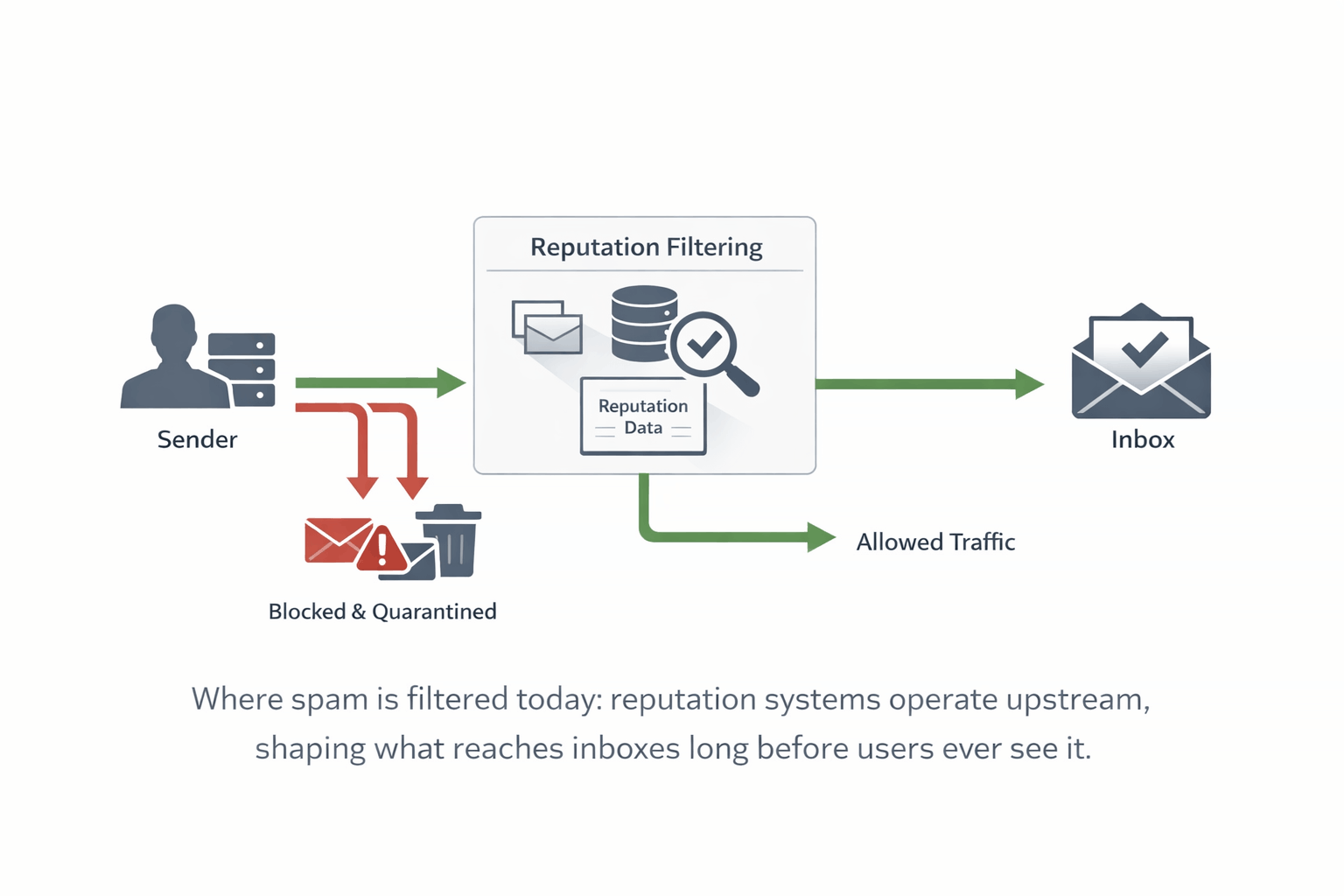

These datasets are consumed by email providers, ISPs, hosting companies, and security vendors worldwide. Decisions about whether to accept, reject, throttle, or scrutinise traffic are often informed by Spamhaus data — even if end users never see its name.

Spamhaus has consistently framed its role as infrastructural rather than editorial, positioning itself as a provider of reputation data rather than a judge of message content.

It describes its role as providing reputation data that informs how network operators assess risk and take action based on infrastructure activity, rather than judging the content of individual messages.

In practical terms, Spamhaus helps answer a single question at internet scale:

Is this sender likely to be abusive?

That framing matters. Spamhaus isn’t deciding whether a message is wanted, correct, or legitimate. It’s assessing risk based on observed infrastructure behaviour — not intent, content, or context.

How spam changed because of it

Early spam relied on volume.

Millions of identical messages, sent cheaply, from disposable infrastructure.

Reputation-based systems made that model fragile:

- IP ranges burned quickly

- Domains were flagged early

- Bulk campaigns stopped paying off

So spam adapted.

Modern spam is typically:

- Lower volume

- More realistic

- Closer to legitimate workflows

Messages look human. Domains look plausible. Sending patterns stay just below obvious thresholds.

This isn’t a failure of filtering.

It’s the result of filtering working.

When obvious abuse becomes expensive, attackers don’t disappear. They move toward subtlety, timing, and trust exploitation instead.

A brief historical aside

One of the most prolific early spammers was Sanford Wallace, often nicknamed “the Spam King”. At his peak in the late 1990s and early 2000s, his operations were responsible for millions of unsolicited emails per day — long before modern reputation systems existed.

What ultimately stopped him wasn’t better content filtering.

It was loss of access.

Wallace was later shut down through lawsuits and permanent injunctions for abusing network infrastructure and circumventing safeguards at scale. The lesson was clear then — and it remains true now:

Spam becomes unsustainable when sending it becomes impossible.

False negatives are not a bug

No reputation system can block everything — and Spamhaus doesn’t try to.

There’s an unavoidable trade-off at the heart of email filtering:

- Block conservatively and accept some abuse slipping through

- Block aggressively and risk breaking legitimate email

Spamhaus-informed systems bias toward avoiding false positives. Blocking real mail has real consequences: missed business messages, broken workflows, and erosion of trust in email itself.

This is the same pattern you see across digital services: incentives shape outcomes — which is why Free vs Paid Email: What You’re Really Paying With matters.

Eliminating all abuse would inevitably cause unacceptable collateral damage to legitimate communication. Like all reputation systems, Spamhaus operates within that constraint.

That means false negatives happen:

- Brand-new domains with no history

- Low-volume, targeted phishing

- Compromised legitimate servers sending small amounts of abuse

These aren’t oversights.

They’re design decisions in a system that prioritises communication over control.

The goal isn’t perfection.

It’s continuity.

What “reputable” email infrastructure usually includes

Email filtering systems don’t rely on a single signal. Reputation is inferred from a combination of technical controls and observed behaviour.

At a minimum, legitimate senders typically implement:

- SPF — Declares which servers are authorised to send mail for a domain

- DKIM — Cryptographically signs messages so tampering can be detected

- DMARC — Tells receivers how to handle mail that fails authentication

- Consistent sending patterns — Predictable volumes and cadence over time

- Clean infrastructure history — IPs and domains not associated with prior abuse

These controls are often mentioned together, but they’re widely misunderstood. They don’t decide whether a message is wanted — they establish whether it’s credible enough to participate in modern email delivery at all.

I break down how SPF, DKIM, and DMARC actually work — and what they do not do — in SPF, DKIM, and DMARC: How Email Authentication Actually Works.

If you want to reduce long-term identity lock-in while still participating in modern trust signals, Why Using Your Own Domain for Email Makes Sense is the practical starting point.

None of these guarantees delivery on their own. Together, they establish baseline trust — and make abuse easier to detect when behaviour changes.

These signals don’t determine whether a message is wanted. They help determine whether it is trustworthy enough to be handled at all.

IP ranges, power, and the lack of arbitration

Spamhaus listings can affect entire IP ranges, not just individual senders. For networks and organisations, that can be disruptive — even when abuse is unintentional, temporary, or caused by a single tenant.

There have been well-documented cases where large hosting providers or email services saw broad portions of their infrastructure affected due to abuse originating from a subset of users. In those moments, the impact wasn’t theoretical: legitimate senders were disrupted alongside malicious ones, and remediation depended on cooperation rather than appeal.

There is also no formal external arbitration. Spamhaus is a private entity making judgement calls that shape global email delivery. Delisting requires remediation and cooperation, but there’s no independent appeals body overseeing decisions.

That concentration of influence is uncomfortable — and arguably unavoidable.

Open systems need shared enforcement points.

Shared enforcement points inevitably accumulate power.

Email works because many actors agree, implicitly, to trust the same signals.

What this means for the wider tech industry

Spamhaus doesn’t just shape inboxes.

It shapes behaviour across the email ecosystem.

For hosting providers, reputation data acts as an external pressure system. Networks that tolerate abuse — even briefly — risk collateral damage across entire IP ranges. That reality pushes providers toward stricter onboarding, faster abuse response, and sometimes pre-emptive restriction.

For email marketing platforms and bulk senders, the message is clearer still: infrastructure hygiene matters more than content. Authentication, warm-up, complaint rates, and sending patterns aren’t best practices — they’re survival requirements.

For privacy-focused services, the trade-off is sharper. Protecting users often means resisting invasive inspection, but reputation systems thrive on signals, patterns, and visibility. Minimising data collection while still participating in shared abuse controls is a delicate balance — and one that can’t be solved by policy statements alone.

Decentralisation, identity, and the limits of reputation

Email is already decentralised — but reputation systems have re-centralised decision-making around a small number of shared signals.

Newer ideas around decentralised identity and alternative trust frameworks often promise to reduce reliance on central authorities. In theory, that could soften the power concentration that systems like Spamhaus represent.

In practice, decentralisation doesn’t remove the need for abuse control — it just relocates it. Any open messaging system still needs shared trust signals, rate limits, and coordination to remain usable at scale.

The lesson from email is sobering: abuse doesn’t disappear in decentralised systems. It forces them to reintroduce coordination, reputation, and enforcement — often in new forms.

Email’s current shape is a preview, not an anomaly.

I’ve been exploring the wider version of this problem — decentralised systems that still need coordination — on my Social Web page.

How Spamhaus has changed over 20+ years

Spamhaus began as a relatively simple blocklist. Over time, it evolved into a broader threat-intelligence operation covering spam, malware, botnets, and abuse infrastructure.

Its scope expanded because spam itself expanded. What started as junk email became part of a wider ecosystem of fraud, phishing, and identity exploitation.

Today, Spamhaus isn’t just about inbox cleanliness.

It’s about containing abuse without breaking the internet.

That’s a much harder problem.

The upside — and the cost

Spamhaus has unquestionably helped:

- Reduce large-scale spam

- Raise the cost of abuse

- Protect billions of mailboxes indirectly

But its success also pushed attackers toward exploiting trust rather than scale. The remaining threats are harder to detect precisely because they look normal.

Spam didn’t go away.

It learned how to blend in.

The uncomfortable conclusion

Spamhaus didn’t fail to stop spam.

It changed what spam could afford to be.

The result is a system where infrastructure abuse is harder, but identity and trust are under greater pressure. That trade-off keeps email usable — but it also explains why modern spam feels less noisy and more dangerous.

Perfect filtering was never the goal.

Keeping email open was.

If you’re following this thread, the best next read is Why Spam Isn’t Disappearing — It’s Just Changing Shape.

Follow future writing

I write about email, spam, phishing, and how digital systems evolve to manage risk rather than eliminate it.

New posts are sent occasionally — no marketing, no noise.