Free vs Paid Email: What You’re Really Paying With

Free email feels effortless, but the real cost often shows up later. This piece explores the hidden trade-offs between free and paid email — from incentives and lock-in to control, privacy, and long-term trust.

Email is one of the few digital tools most of us rely on every single day, yet rarely stop to question. We pick a provider once—often years ago—and then build our online lives around it. Messages, logins, archives, recovery emails, and personal history all quietly accumulate in one place.

When people talk about free vs paid email, the conversation usually stops at price. Why pay when Gmail works fine? What do you really get for a monthly fee?

But cost is the least interesting difference.

The real distinction is what you’re paying with when you don’t pay with money.

Gmail and other free email providers aren’t free in any meaningful sense. They’re funded by incentives that shape product decisions, data handling, feature priorities, and long-term control. Paid services, meanwhile, ask for cash—but often remove pressure to monetise attention, behaviour, or dependence. That difference isn’t always obvious, but it matters more the longer email becomes part of your digital identity.

What “free” really pays for

Email is often described as “free”, but that framing hides more than it explains.

Running a global email service is expensive. Storage, spam filtering, abuse prevention, uptime guarantees, security teams, compliance, and constant infrastructure upgrades all cost real money. When a user isn’t paying directly, the service still has to recover those costs somehow.

That doesn’t automatically mean exploitation or bad intent. But it does mean the incentives are different. Decisions about features, defaults, data retention, and product direction are shaped by what sustains the business — not necessarily what gives the individual user the most control or clarity.

Over time, those incentives quietly influence how email behaves.

Paid email changes the incentives

When you pay for email, the relationship is simpler.

You’re the customer, not the input. The service is accountable to you in a direct way: if it fails, degrades, or drifts in a direction you don’t agree with, you can leave and take your address with you. That doesn’t guarantee perfection, but it does change the centre of gravity.

That ability to leave without losing your identity depends on separating your email address from the provider — something I explore in more detail in Why Using Your Own Domain for Email Makes Sense.

One of the quietest forms of lock-in is the email address itself, especially when it’s owned by the provider rather than the user.

One of the quietest forms of lock-in is the email address itself, especially when it’s owned by the provider rather than the user.

Paid email providers still make trade-offs. They still prioritise features, make product bets, and sometimes get things wrong. But their survival depends on retaining trust, not extracting value from attention, metadata, or behavioural signals.

That difference matters most over long periods of use.

Free and paid email services optimise for different priorities, not different kinds of people.

If you want to see how these differences show up in practice, I’ve written in more detail about Gmail, Proton Mail, StartMail, Tuta Mail and Fastmail separately.

Why this compounds over time

Email isn’t something you replace often. Addresses accumulate history, logins, subscriptions, work relationships, and personal records. The longer you keep an address, the more expensive it becomes — socially and practically — to change it.

That’s why early choices matter. A “good enough” free service can quietly become a dependency, even if it no longer aligns with how you think about privacy, control, or independence.

Paid email doesn’t eliminate lock-in, but it tends to make it more explicit. You know what you’re paying, what you’re getting, and what would happen if you stopped.

And that clarity is often the real value.

Who paid email actually makes sense for (and who it doesn’t)

Paid email isn’t a universal upgrade, and it doesn’t need to be.

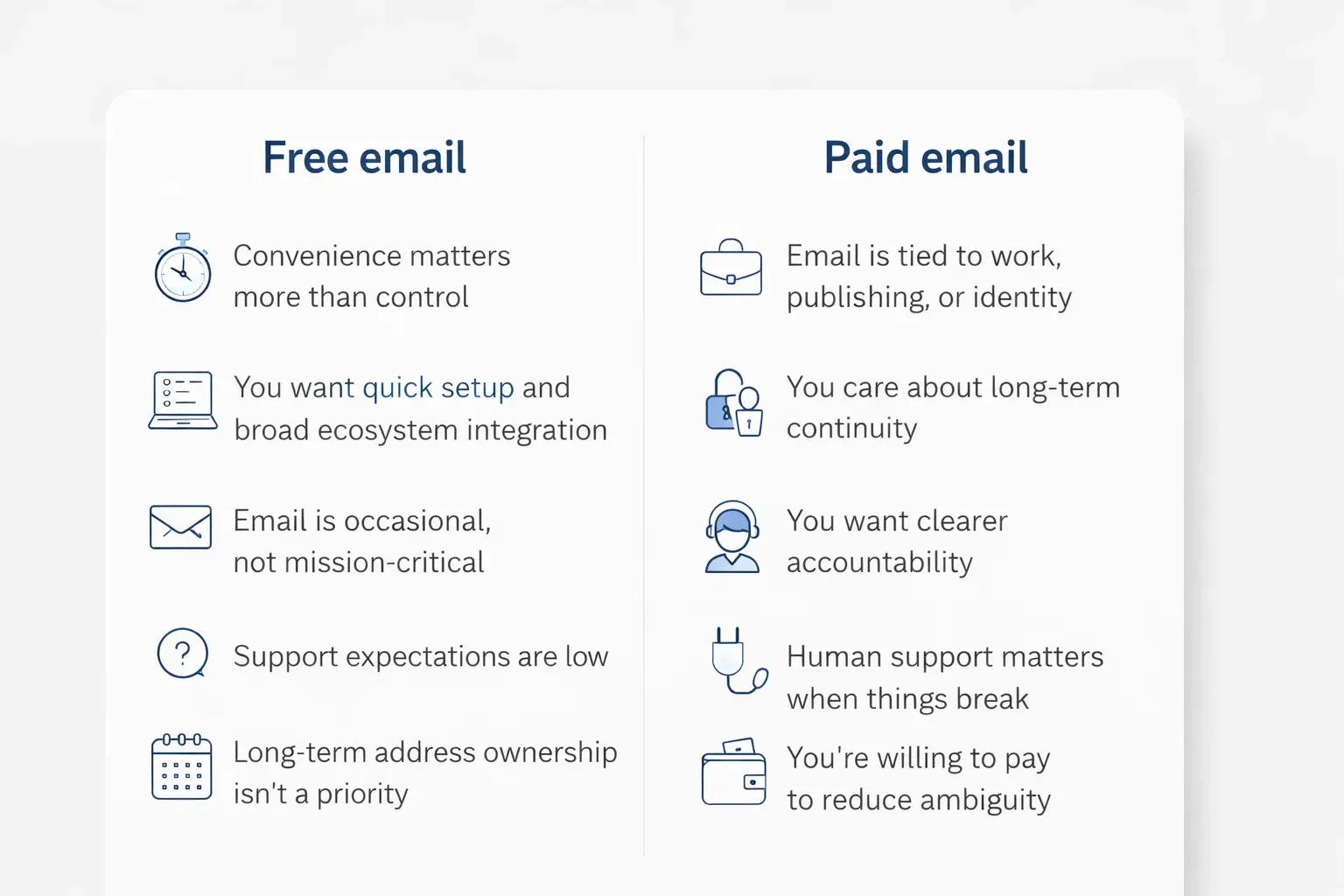

For people who treat email as a lightweight utility — a place for occasional messages, receipts, and logins — free services can be entirely sufficient. They’re convenient, familiar, and deeply integrated into wider ecosystems that many people already rely on.

Paid email starts to make sense when email becomes something you depend on.

That might be because your inbox is tied to work, publishing, or long-term projects. It might be because you care about keeping the same address for decades, not just years. Or it might be because you’ve grown more cautious about how much of your digital life sits behind a single account you don’t fully control.

In those cases, paying for email isn’t really about features. It’s about intent.

You’re choosing a relationship where the service exists to serve you, not to monetise you indirectly. You’re paying to reduce ambiguity — about who the customer is, how decisions are made, and what happens if your priorities change.

Another difference that often only becomes visible when something goes wrong is support.

Most free email providers don’t offer access to real, accountable human support. Help is typically limited to automated systems, community forums, or generic documentation — even when the issue involves account access, security flags, or lost data. For a service that often acts as the recovery key to someone’s entire digital life, that absence carries real risk.

That doesn’t make paid email “better” in the abstract. It simply makes it more aligned with certain kinds of use — particularly where continuity, accountability, and control matter.

Free email works best when convenience outweighs consequence. Paid email tends to make more sense when email becomes something you depend on rather than something you occasionally use.

And understanding which category you fall into is often more important than which provider you choose.

Get the weekly email

A short weekly roundup on email, privacy, and digital trust. No promos. Unsubscribe anytime.