Your Email Address Is Still Your Weakest Privacy Link

Privacy rarely fails through dramatic hacks. It erodes quietly as the same email address is reused across accounts, services, and years of digital life — turning a simple inbox into an identity anchor.

Most people think privacy failures start with hacks.

A breached database. A compromised provider. A headline about leaked passwords or stolen data. Those events feel dramatic, visible, and external — something that happens to you.

But the more common privacy failure is quieter.

It happens long before any breach. It happens every time the same email address is reused, trusted, and quietly stitched across accounts, services, and years of digital life. No attacker needs to break in when your identity is already neatly linked together.

Your email address has become more than a way to receive messages. It’s a login, a recovery mechanism, a record of transactions, and often the single thread tying your online activity together. Once that thread is exposed, everything attached to it becomes easier to map, target, and exploit.

That’s why email remains the weakest link in otherwise careful privacy setups. Not because email itself is insecure, but because we’ve allowed a single address to carry too much weight — across too many systems — for too long.

Why this matters more than ever

With Data Privacy Day approaching, it’s worth noting that much of the conversation focuses on tools, settings, and new features — yet one of the most persistent privacy failures isn’t technical at all.

Modern privacy tools have improved dramatically. Encrypted email, better spam filtering, stronger authentication, and more awareness of tracking all help reduce risk. But most of these protections operate around the inbox, not at the identity layer beneath it.

When one email address is reused everywhere, even strong tools can’t prevent correlation — which is why separating addresses from providers and contexts matters more than most people realise.

Activity stays linkable. Recovery flows stay predictable. Trust concentrates around a single point of failure.

Privacy doesn’t usually collapse through a dramatic breach. It erodes through convenience.

Two quiet ways privacy unravels

Consider how this usually plays out in practice.

Someone uses the same email address for banking, shopping, newsletters, cloud storage, and social accounts. Years later, that address appears in a data breach — not because of anything sensitive, but because a low-risk service didn’t take security seriously. Nothing dramatic happens. No money is lost. But the address is now permanently associated with a bundle of accounts and behaviours that were never meant to be linked.

Or take a more mundane case. A routine account recovery email lands in the inbox — the kind people barely think about anymore. It reveals which services are connected, which ones matter, and how access can be restored. The inbox becomes a map of digital life, not just a place messages arrive. Anyone who gains access doesn’t need to guess where to go next — the path is laid out for them.

Neither of these scenarios relies on advanced attacks or technical exploits. They work because email addresses have quietly become identity anchors, reused by default and trusted everywhere.

That’s the weakness most privacy discussions miss.

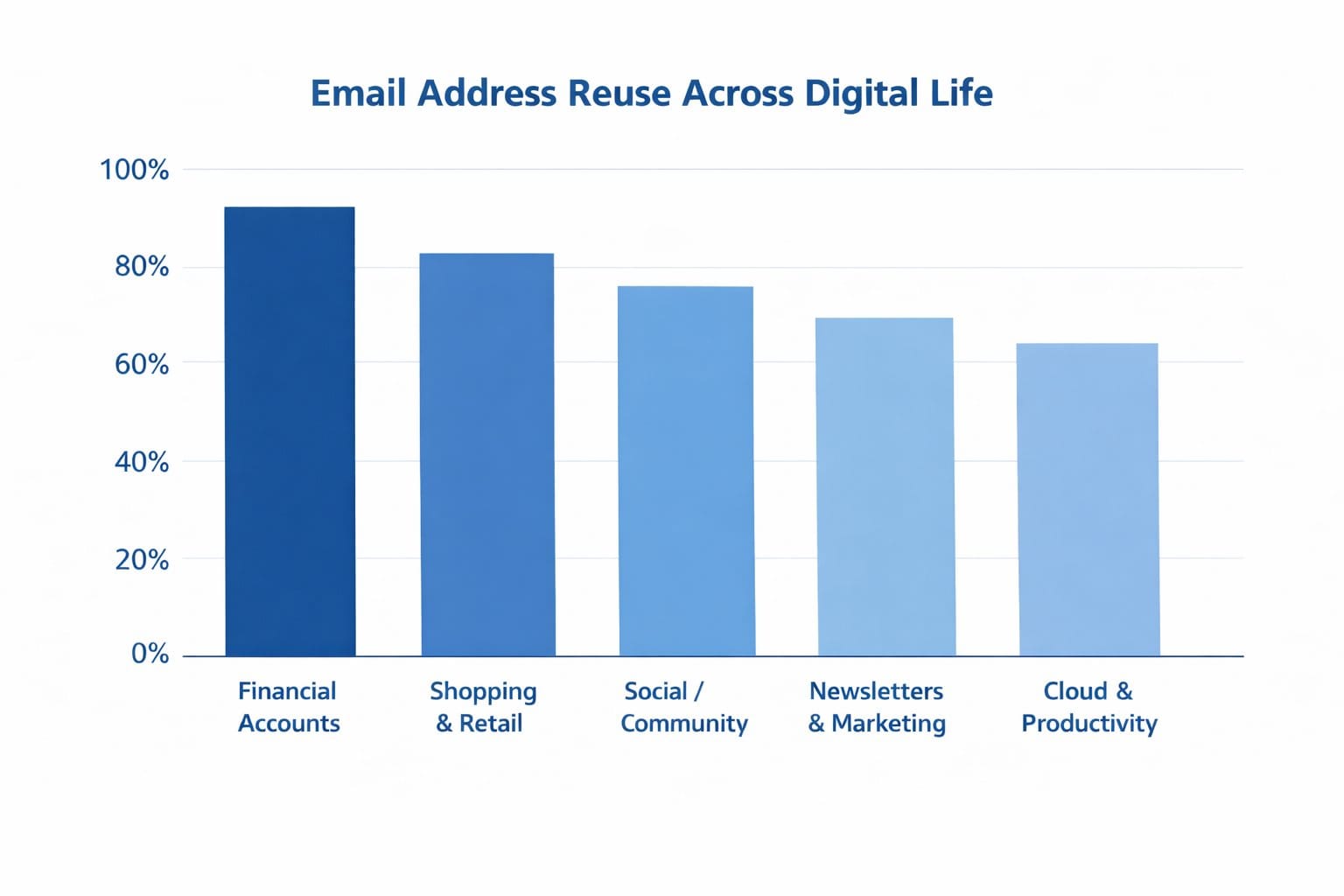

Email address reuse is one of the most common — and least visible — privacy risks online.

Indicative figures based on aggregated findings from industry surveys, breach analysis reports, and email provider usage data. Percentages vary by region and service.

These patterns align closely with findings in the Verizon Data Breach Investigations Report, which consistently shows email-based identity exposure as a primary risk multiplier.

Email as identity, not just communication

Email was never meant to carry this much weight.

It started as a way to exchange messages, but over time it quietly became something else: a universal identifier. Today, your email address is how services recognise you, reset your access, confirm your activity, and establish continuity over years — sometimes decades.

In practice, an email address now functions as:

- A login credential

- An account recovery channel

- A transaction record

- A long-term identifier tied to behaviour and history

That makes it far more than a mailbox. It’s an identity anchor.

Once an email address is established, everything else tends to attach itself to it. New services ask for it by default. Recovery flows depend on it. Notifications, alerts, and confirmations all route through the same place. Over time, the inbox becomes a living index of your digital life.

This shift didn’t happen because email is uniquely insecure. It happened because it’s convenient, universal, and assumed to be stable. But stability cuts both ways. The same permanence that makes email useful also makes it difficult to contain when things go wrong.

Why privacy tools don’t solve this by default

Modern privacy tooling has improved dramatically. Encryption is more accessible. Authentication is stronger. Spam filtering is far more effective than it once was. On paper, the ecosystem looks healthier than ever.

But most of these protections operate around email, not at the identity layer beneath it.

Encryption protects message content, not account linkage. Strong passwords and passkeys protect access, not correlation. Even privacy-focused providers still rely on your email address as the primary way services recognise and recover your account.

As long as the same address is reused across contexts, activity remains linkable — even if individual messages are secure. Recovery paths stay predictable. Trust continues to concentrate around a single point.

This is why privacy failures so often feel disproportionate. The issue isn’t that one tool failed. It’s that too much depended on one identifier.

Privacy doesn’t usually break because a system was poorly designed. It breaks because we asked a single address to do everything.

How most people leak privacy without noticing

Most privacy failures don’t feel like failures at all.

They look like convenience. Using one familiar email address everywhere. Letting account recovery defaults stand. Treating the inbox as a neutral utility rather than a sensitive control surface.

Over time, this creates patterns that are easy to overlook:

- The same email address used for banking, shopping, newsletters, and forums

- Recovery emails revealing which services matter most

- Years of alerts, confirmations, and receipts accumulating in one place

- A single inbox quietly documenting behaviour, relationships, and priorities

None of this requires malicious intent or technical failure. It emerges naturally from how modern services are designed to recognise and remember users.

The result is that privacy exposure grows gradually, not suddenly. By the time it’s visible, it’s usually already structural.

The real fix isn’t perfection — it’s separation

Privacy is often framed as a pursuit of flawlessness: perfect tools, perfect habits, perfect awareness. In reality, that model doesn’t scale.

What does scale is separation.

Separating identities by context. Separating high-risk from low-risk activity. Separating long-term access from disposable interaction. The goal isn’t to eliminate mistakes — it’s to limit how much damage any single mistake can cause.

This is the same principle that underpins modern security design elsewhere. Systems are built assuming failure will happen, and are judged by how well they contain it.

Email addresses are no different. When one address is treated as a master key, failure cascades. When addresses are segmented, exposure becomes local instead of global.

That’s the shift most privacy conversations skip.

What actually improves privacy outcomes

The most meaningful privacy improvements tend to be quiet and unglamorous. They don’t rely on vigilance or constant decision-making. They rely on reducing how much any one element is trusted by default.

In practice, that means:

- Fewer services sharing the same identifier

- Clear boundaries between sensitive and low-risk accounts

- Recovery paths that don’t expose the entire account landscape

- Designing identity so it can fail without collapsing everything attached to it

None of this requires abandoning email or chasing novelty. It requires treating email addresses as part of identity architecture, not just contact details.

The uncomfortable truth

Email remains central to digital life because it works. It’s universal, durable, and widely trusted. That isn’t a weakness — but it does come with consequences.

As long as a single email address is allowed to function as login, recovery mechanism, audit trail, and long-term identifier all at once, privacy will remain fragile — no matter how good the surrounding tools become.

Privacy doesn’t usually fail because people don’t care. It fails because systems reward convenience over containment.

Final thoughts

Privacy isn’t something you bolt on once and forget. It’s something that emerges — or erodes — from how identities are designed and reused over time.

If there’s one takeaway worth holding onto, it’s this:

the quiet risks matter more than the dramatic ones.

Your email address is still one of the strongest signals tying your digital life together. Treating it with the same care you give passwords or devices isn’t paranoia — it’s proportionate.

And once you see email that way, a lot of modern privacy problems start to make more sense.

Get the weekly email

A short weekly roundup on email, privacy, and digital trust. No promos. Unsubscribe anytime.