Have I Been Pwned: What Data Breaches Mean for Your Email

Data breaches don’t just leak passwords — they expose email addresses that quietly tie together your digital life. Here’s how Have I Been Pwned helps you understand the risk.

Every few months, another headline announces that millions — sometimes billions — of accounts have been exposed in a data breach. Most of us shrug, change a password (maybe), and move on.

Then one day you type your email address into Have I Been Pwned and see a list of companies you once trusted — now sitting in a breach database.

That moment feels personal. But it’s not just about one hacked website. It’s about how fragile our digital identity has quietly become.

This article isn’t a tutorial on how to use the site. It’s about what HIBP reveals about the bigger system we all rely on.

What Have I Been Pwned Actually Does

Have I Been Pwned (often shortened to HIBP) is a public breach-notification service created by security researcher Troy Hunt.

In simple terms, it:

- Collects and verifies data from known breaches

- Lets you check whether your email address appears in those datasets

- Offers alerts so you’re notified if your address shows up in future breaches

HIBP does not hack companies. It doesn’t see your current inbox or passwords. It works with breach data that’s already circulating — often shared in security communities, posted online, or traded in criminal forums.

Think of it less as a detector, and more as a public record of where things have already gone wrong.

Why Your Email Address Is the Real Issue

When you see your email listed in multiple breaches, the instinct is to think:

“That company messed up.”

True. But there’s a deeper problem.

Your email address is:

- Your login for dozens (or hundreds) of services

- Your password reset channel

- Your identity proof for banks, shops, apps, and social media

It’s not just an inbox. It’s the anchor of your digital life.

So when your email appears in breach after breach, attackers learn something important:

This address is real, active, and tied to lots of accounts.

That makes you a target for:

- Phishing emails tailored to services you use

- Credential stuffing attacks (trying leaked passwords on other sites)

- Account recovery abuse

HIBP doesn’t create this risk. It just makes it visible.

For context, my own long-running email address shows up in several historic breaches. Most of them are years old, tied to services I’d forgotten I’d ever signed up to. That’s normal if you’ve used the same address across the web for a long time — and it’s exactly why I now recommend keeping your primary address off the open internet as much as possible. Use aliases where you can, and for day-to-day signups I’ve found tools like DuckDuckGo Email Protection useful, because it forwards mail on without exposing your real address to every site you touch.

What It Means If You Show Up in a Breach

Seeing your email in a breach does not automatically mean someone is inside your accounts right now.

It usually means one of these things:

- A service you used stored your data insecurely

- Your email (and possibly password hash) was exposed

- That data is now circulating somewhere outside the company

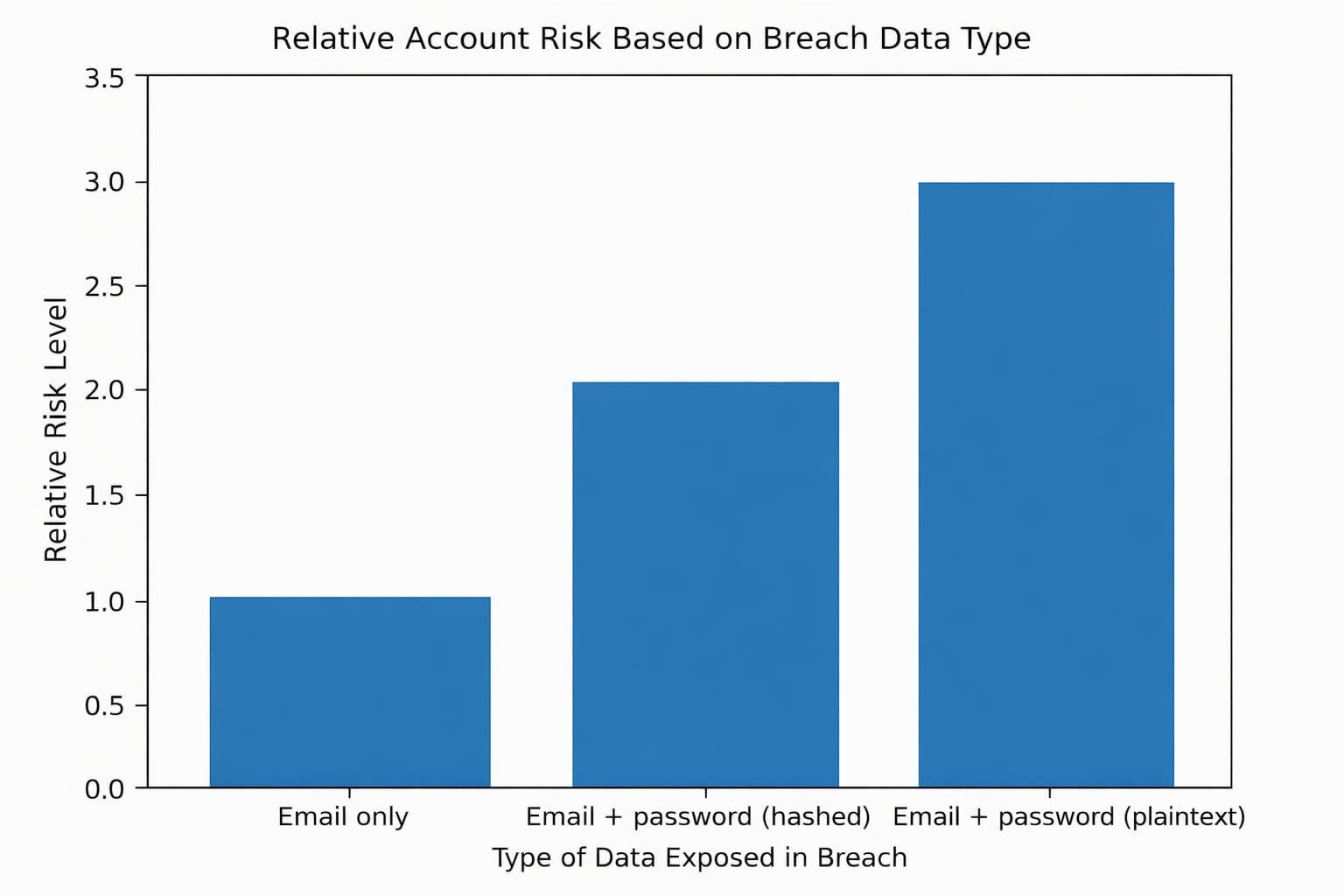

The risk depends on what was leaked:

| Data Exposed | Risk Level | Why |

|---|---|---|

| Email only | Low–Medium | More phishing and spam |

| Email + password (hashed) | Medium–High | Risk if password reused |

| Email + password (plaintext) | High | Immediate risk across reused accounts |

Here’s the same idea visually — exposure risk jumps when passwords are included.

The biggest danger isn’t the breach itself — it’s password reuse. If you’ve used the same or similar passwords elsewhere, attackers will try them.

This is why password reuse is one of the most dangerous habits online — a single breach can cascade across dozens of accounts.

What HIBP Can’t Tell You

HIBP is powerful, but it has limits.

It can’t tell you:

- Whether attackers have already accessed your specific accounts

- How widely the stolen data has been traded

- About breaches that haven’t yet become public

- Whether your email is being used in targeted phishing campaigns

In other words, it shows known exposure, not the full picture.

Treat it as a warning system, not a complete security audit.

What To Do If You Appear in a Breach

Here’s the practical part — the bit most people skip.

1. Change Passwords — But Strategically

If a breached service used the same password as anything else:

- Change that password everywhere it was reused

- Make sure new passwords are unique

This is where a password manager stops being optional and becomes essential.

2. Turn On Two-Factor Authentication (2FA)

2FA dramatically reduces the damage of leaked passwords. Even if someone has your password, they still can’t log in without your second factor.

Focus first on:

- Email accounts

- Banking

- Primary social media

- Cloud storage

3. Treat Your Email as a High-Value Asset

Your email is the key to resetting everything else — which is why protecting it properly matters. Protect it like you would your bank account:

- Strong, unique password

- 2FA enabled

- Recovery options reviewed and up to date

4. Expect More Phishing

After breaches, phishing increases. You may see emails claiming:

- “Unusual login detected”

- “Reset your password now”

- “Security alert from [company name]”

HIBP results often explain why those emails are suddenly more convincing.

The Bigger Lesson: Breaches Are Structural, Not Exceptional

HIBP is popular because breaches feel like rare disasters. They aren’t.

They’re a normal by-product of:

- Centralised identity systems

- Massive user databases

- Password-based authentication

- Email as the universal recovery mechanism

In that world, your data leaking somewhere isn’t shocking. It’s statistically likely.

HIBP doesn’t just show that companies fail. It shows that the model itself is fragile.

Privacy Is a Process, Not a Checkbox

Checking your email on Have I Been Pwned isn’t about fear. It’s about awareness.

It reminds you that:

- Your email address is powerful

- Password reuse is dangerous

- Identity risk accumulates quietly over time

No single tool fixes that. But tools like HIBP help you see the exposure so you can reduce it.

The goal isn’t to avoid every breach. That’s unrealistic.

The goal is this:

When breaches happen — and they will — they shouldn’t be able to take your digital life with them.

Get the weekly email

A short weekly roundup on email, privacy, and digital trust. No promos. Unsubscribe anytime.