SPF: What It Really Proves — and Why It Fails So Often

SPF doesn’t verify who sent an email — it only confirms that a server was allowed to deliver it. That distinction explains why SPF passes during phishing, fails during forwarding, and can’t be treated as a trust signal on its own.

SPF (Sender Policy Framework) is often described as an authentication system, but that label hides what it actually does. SPF doesn’t prove who wrote an email, and it doesn’t verify the identity a recipient sees in their inbox. What it proves is much narrower: whether the server that delivered a message was authorised to send mail on behalf of a domain.

It’s a permission check, not an identity guarantee.

SPF is also where many people first get stuck. Not because it’s complex, but because it fails quietly and for reasons that aren’t obvious. People often encounter it while trying to fix “unauthenticated” warnings, staring at DNS records late at night, unsure whether the problem is syntax, policy, forwarding, or something else entirely.

Understanding SPF starts with accepting its limits.

SPF is only one part of a broader system. If you want the full context of how SPF, DKIM, and DMARC fit together, this earlier post explains how email authentication actually works.

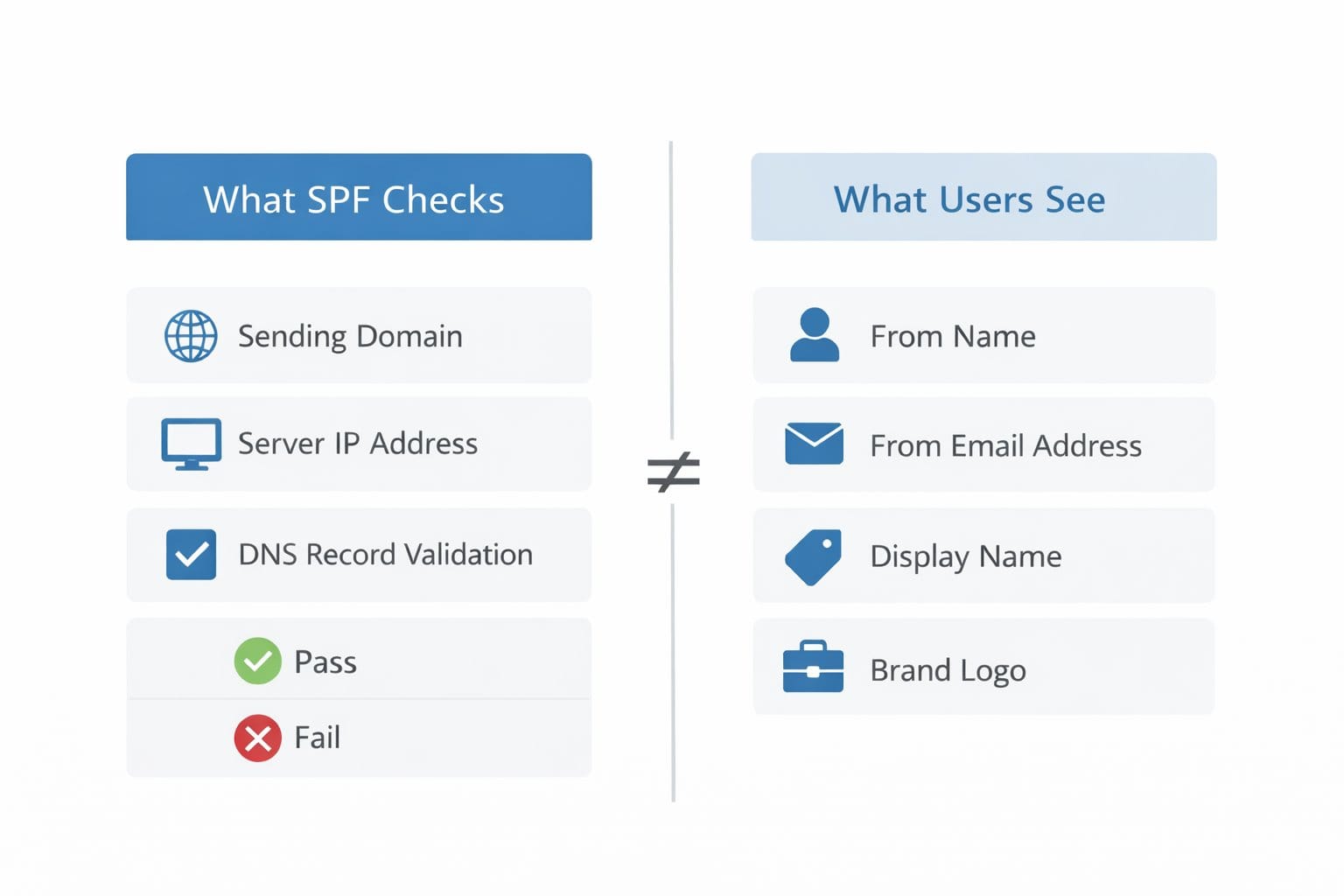

What SPF actually checks — and what it ignores

At a technical level, SPF is evaluated during delivery, not after a message has arrived. When a mail server receives an email, the receiving server looks at the IP address that connected to it, and at the domain used for mail routing behind the scenes — known as the envelope sender or Return-Path.

It then checks the SPF record published in DNS for that routing domain to see whether the sending IP is authorised. If it is, SPF passes. If it isn’t, SPF fails.

That’s it.

An SPF record is just a single line of text published in DNS. A simple example looks like this:

v=spf1 ip4:192.0.2.10 include:_spf.google.com -all

Example SPF record published in DNS, declaring which servers are authorised to send mail for a domain

Read in plain English, this says: mail from this domain is allowed to come from this server, and from Google’s mail servers — anything else should be rejected.

SPF does not examine the message content. It doesn’t validate headers. And crucially, it doesn’t verify the visible From address a human sees in their inbox. SPF checks the delivery path, not the identity presented to the recipient.

This is where confusion often begins. Because phishing attacks abuse familiar-looking sender identities, people assume SPF protects the visible sender. In reality, SPF evaluates a technical return path most users never see. A message can pass SPF perfectly while still presenting a misleading or unexpected identity.

SPF is effective at controlling infrastructure. It’s far less effective at protecting human trust.

Why legitimate email so often fails SPF

SPF’s biggest weakness isn’t misconfiguration. It’s that the modern email ecosystem no longer matches the assumptions SPF was built on.

SPF works only if the server that delivers a message is the same server that was authorised to send it. That assumption held when email mostly travelled directly from sender to recipient. Today, it rarely does.

Forwarding is the simplest example. When an email is forwarded, it’s typically re-sent by a different server — one that isn’t listed in the original sender’s SPF record. The message hasn’t changed. The intent hasn’t changed. But the delivery path has, and SPF fails as a result.

Mailing lists create the same problem in a different way. Many lists redistribute messages from their own infrastructure without rewriting the envelope sender. From SPF’s perspective, the list server now looks unauthorised, even though everyone involved is behaving legitimately.

SPF can’t distinguish between malicious impersonation and normal relaying. All it sees is an IP address that doesn’t match what DNS says should be sending.

Some systems try to work around this by rewriting the envelope sender or using techniques like bounce address rewriting. These approaches help SPF pass, but they introduce complexity and trade-offs — and they still don’t solve the underlying identity problem.

That’s why modern email authentication rarely relies on SPF alone. DKIM helps authenticate the message itself rather than the sending server, DMARC ties those signals to the visible identity a user sees, and newer approaches like ARC help preserve authentication results as messages pass through forwarding systems.

SPF isn’t broken. It’s doing exactly what it was designed to do. The problem is that email has outgrown the narrow model SPF relies on.

Why SPF passing doesn’t mean a message is trustworthy

One of the most persistent misunderstandings around SPF is the belief that a “pass” result implies legitimacy. It doesn’t.

An SPF pass only means that the server which delivered the message was authorised to send mail for the domain it claimed during delivery. It says nothing about who wrote the message, whether the sender is honest, or whether the recipient should trust what they’re reading.

This is why SPF can pass during phishing and impersonation attacks. An attacker doesn’t need to spoof infrastructure if they control some legitimate sending domain. As long as the message is sent from an authorised server for that domain, SPF will pass — even if the visible sender identity is misleading or deliberately confusing.

SPF is blind to context. It doesn’t evaluate intent, familiarity, or relevance. It simply confirms that a delivery path was permitted.

That’s why “SPF passed” often appears in message headers alongside obvious abuse. The check is working — but the job it’s doing is narrower than most people expect.

Why SPF was never meant to stand alone

SPF emerged in the early 2000s, when most email was sent directly from a small number of clearly owned servers. It was designed to answer a single operational question: is this system allowed to send mail for this domain?

It was never intended to establish identity in the way modern inboxes now expect.

As email infrastructure became more complex — with forwarding, cloud services, shared platforms, and mailing lists — SPF stayed largely the same. Expectations shifted, but the mechanism didn’t.

That limitation is the key to understanding why SPF needs to be paired with other signals. SPF can declare sending intent. It can’t vouch for message integrity or visible identity. Those gaps are filled elsewhere.

SPF says, “this server is allowed to send.”

It does not say, “this message is who it claims to be.”

Where SPF fits — and where it stops

SPF remains essential. It blocks a large class of low-effort abuse and misconfigured sending. It gives receiving systems a baseline declaration of intent. Without it, impersonation would be far easier to scale.

But SPF is not a trust mechanism. It’s infrastructure hygiene.

Treating SPF as a guarantee leads to false confidence when it passes — and unnecessary alarm when it fails. Understanding its limits makes it far more useful than expecting it to do a job it was never designed to perform.

This article is the first in a series examining how email authentication actually works — starting with SPF, and then moving through DKIM, DMARC, and the limits of trust signals more broadly.

SPF explains who is allowed to send.

The rest of the system exists to answer the harder question: who should be believed?

SPF is only one piece of modern email authentication.

The SPF specification is maintained at OpenSPF.org.

Get the weekly email

A short weekly roundup on email, privacy, and digital trust. No promos. Unsubscribe anytime.