SPF, DKIM, and DMARC: How Email Authentication Actually Works

Email authentication relies on SPF, DKIM, and DMARC — a set of interlocking systems — but most people misunderstand what they really do, and what they don’t protect.

Why email needs authentication at all

Email was never designed with trust in mind.

It was built in an era when the network was small, cooperative, and largely academic. The assumption was simple: if a message arrived, it probably came from who it said it came from. That assumption no longer holds — and hasn’t for a long time.

At a technical level, nothing in basic email forces a sender to prove who they are. The From address you see in your inbox is just a label. Without additional, domain-level checks, anyone can claim to be your bank, your employer, or you.

That doesn’t mean email is “broken”. It means it evolved faster than its original design anticipated.

Email authentication exists to fill that gap. Not to make email perfectly secure — that’s unrealistic — but to reduce impersonation, limit abuse, and give receiving systems something concrete to evaluate instead of blind trust.

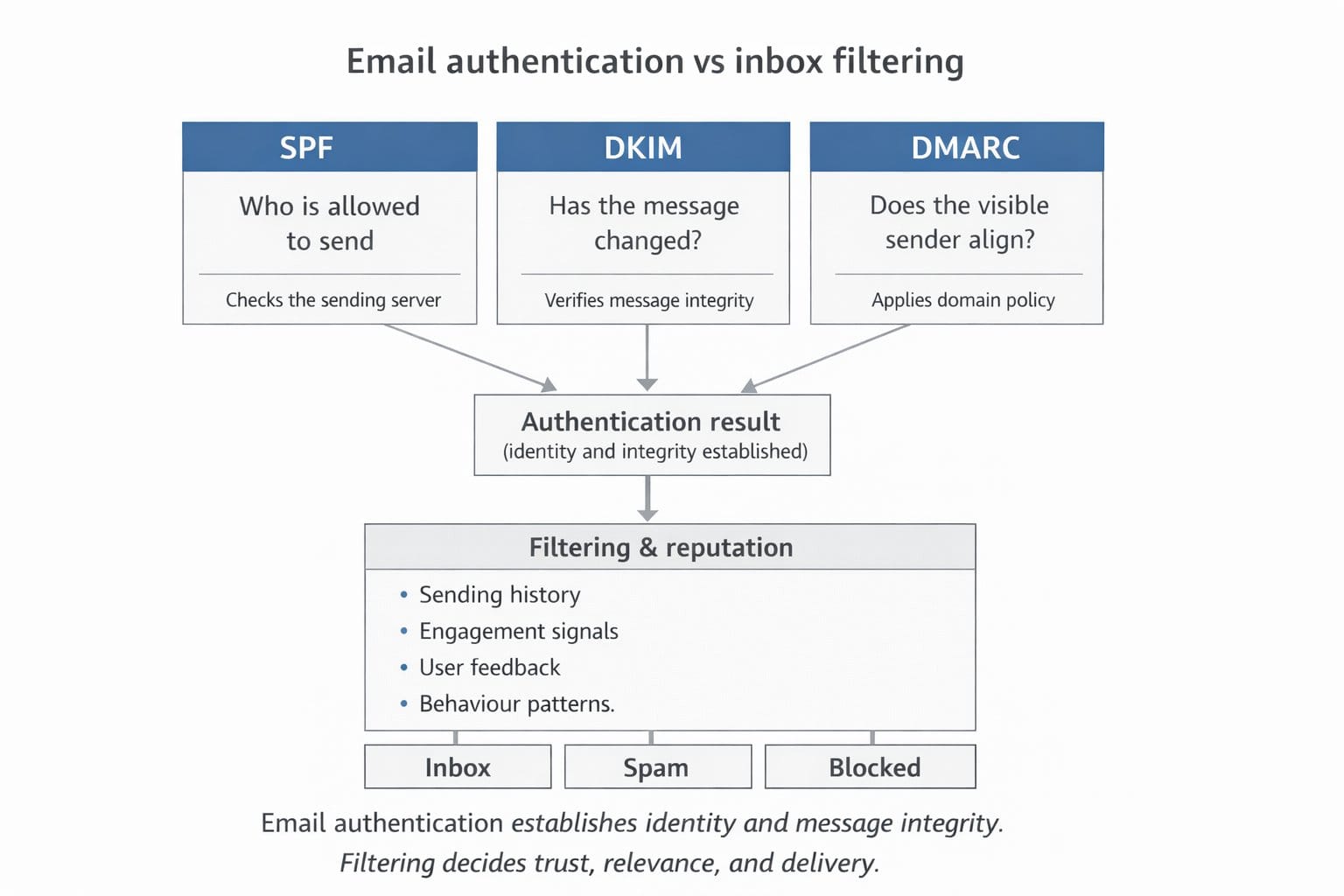

It’s also important to be clear about what authentication is not. These mechanisms don’t decide whether a message is wanted, useful, or legitimate in a broader sense. They don’t stop spam on their own. They don’t prevent scams from existing.

What they do is answer a narrower question:

Is this message allowed to speak on behalf of this domain — and can that claim be verified?

Everything else — filtering, reputation, user behaviour — is layered on top of that answer.

Understanding email authentication starts with accepting that email is a trust system built on signals, not guarantees. The goal isn’t perfection. It’s making abuse harder, more expensive, and easier to spot.

SPF: who is allowed to send mail for a domain

SPF (Sender Policy Framework) is about permission

At its simplest, SPF answers one question: is this server allowed to send email on behalf of this domain?

Domain owners publish a list of approved sending servers in DNS. When an email arrives, the receiving mail system checks the IP address that delivered the message against that list. If the server is authorised, SPF passes. If not, it fails.

That sounds straightforward — and in isolation, it is.

The important detail is what SPF actually checks. SPF doesn’t look at the message content. It doesn’t verify the visible From address you see in your inbox. It checks the envelope sender — the behind-the-scenes return address used during mail delivery.

This distinction matters more than most people realise.

Because SPF is tied to the delivery path, it’s fragile. Forwarding breaks it. Mailing lists break it. Any system that relays a message from one server to another without rewriting the envelope can cause SPF to fail — even if the message itself is perfectly legitimate.

That’s why SPF on its own is not enough. A message can pass SPF while pretending to be someone else, or fail SPF despite being genuine.

SPF is still essential. It prevents a large class of low-effort impersonation and misconfigured sending. But it was never meant to stand alone. It’s one signal in a wider system — useful, necessary, and incomplete by design.

In practice, SPF works best when it’s treated as a declaration of intent, not a final judgement. It says, “these servers are allowed to speak for me,” but it doesn’t prove that the message itself hasn’t been altered, or that the visible sender identity is honest.

Those gaps are filled elsewhere — which is where DKIM comes in.

For a deeper look at what SPF actually proves — and why it fails so often — see the full SPF explainer.

DKIM: proving the message wasn’t altered

If SPF is about permission, DKIM (DomainKeys Identified Mail) is about integrity.

DKIM allows a sending domain to cryptographically sign an email. That signature is added to the message headers before it leaves the sender’s system. When the message arrives, the receiving server retrieves a public key from DNS and checks that the signature matches.

If it does, two things are established.

First, the message hasn’t been altered in transit. The headers and body are the same as when the sender signed them. Second, the domain listed in the signature took responsibility for the message at the point it was sent.

This is a crucial difference from SPF. DKIM is tied to the message itself, not the delivery path. That means it usually survives forwarding. A message can pass DKIM even if it passes through multiple servers along the way.

That resilience is why DKIM became so important as email grew more complex.

But DKIM has its own limitations. It doesn’t care what the visible From address says. A message can be correctly signed by one domain while claiming to be from another. As far as DKIM alone is concerned, that’s allowed.

DKIM can also fail in subtle ways. Poorly configured systems, broken mailing lists, or overzealous security gateways can modify headers or message formatting just enough to invalidate a signature. When that happens, the message looks suspicious even if the intent was benign.

So, like SPF, DKIM is powerful but incomplete.

It tells receiving systems, “this message is intact, and this domain vouches for it.” What it doesn’t say is whether that domain is the one the recipient expects to hear from.

Closing that gap — between technical authenticity and visible identity — is where DMARC comes in.

For a deeper look at what DKIM actually proves — and what it deliberately ignores — see the full DKIM explainer.

Tools like email masking and forwarding change how reputation is applied — something I look at in DuckDuckGo Email Protection: What It Solves (and What It Doesn’t).

DMARC: tying identity to policy

DMARC exists because SPF and DKIM, on their own, aren’t enough.

Both can pass while still allowing impersonation. SPF checks the delivery path. DKIM verifies the message integrity. Neither guarantees that the domain signing or sending the message is the same one the recipient sees in the From address.

DMARC (Domain-based Message Authentication, Reporting & Conformance) fixes that.

At its core, DMARC introduces alignment. It requires that the domain in the visible From address matches the domain used by SPF, DKIM, or both. If that alignment isn’t there, the message fails DMARC — even if SPF or DKIM pass individually.

That distinction is subtle, but it’s the reason DMARC matters.

DMARC also adds something the earlier mechanisms deliberately avoided: policy. Domain owners can state what they want receivers to do when authentication fails. Start with monitoring only. Move to quarantining suspicious messages. Eventually, reject them outright.

This gradual approach is intentional. Email ecosystems are messy, and DMARC recognises that enforcing identity too aggressively without visibility can break legitimate mail. That’s why reporting is built in from the start.

Those reports — aggregated summaries of pass and fail results — are often ignored or misunderstood. In practice, when collected, they’re one of the most valuable parts of DMARC. They show where mail is really coming from, what’s failing, and which systems are pretending to be you.

Once DMARC is in place and enforced, something important changes. The visible From address stops being a cosmetic label and starts carrying weight. Domains become accountable for how they’re used — or abused — in a way that wasn’t possible before.

That doesn’t mean abuse disappears. It means it becomes harder to scale, easier to detect, and more expensive to sustain.

DMARC doesn’t make email safe. It makes identity meaningful. And in a system built on trust signals, that’s a big step forward.

For a deeper look at what DMARC actually proves — and why it fails so often — see the full DMARC explainer.

Why passing everything still doesn’t guarantee the inbox

It’s tempting to think that once SPF, DKIM, and DMARC are set up correctly, email delivery becomes predictable. In reality, authentication is only the starting point.

Passing these checks tells receiving systems that a message is technically credible. It doesn’t say anything about whether the message is wanted, trustworthy, or worth attention.

Modern filtering systems, operated by individual mail providers, care deeply about behaviour. How often messages arrive from a sender. Whether recipients open or ignore them. How many people mark them as spam. Whether volume spikes suddenly or drifts upward over time. These signals matter just as much — often more — than authentication alone.

Some providers layer these behavioural systems on top of stricter privacy models — an approach visible in services like Proton Mail.

Reputation is built slowly and lost quickly. A domain that passes every check can still end up in spam if its sending patterns look abusive or careless. Equally, a well-behaved sender with occasional technical failures may still land in the inbox because history and engagement work in their favour.

This is where a lot of confusion comes from. People look at headers, see “everything passed,” and assume something is broken when delivery isn’t perfect. What’s actually happening is a judgement call based on context, not a binary rule set.

Authentication proves you’re allowed to speak. It doesn’t guarantee anyone wants to listen.

That’s by design. Email would be unusable if technical correctness alone decided delivery. Filters exist to balance identity, behaviour, and user choice — and no single signal gets to dominate.

Understanding that distinction helps set realistic expectations. Authentication reduces risk and prevents impersonation. Inbox placement is earned over time.

What email authentication does — and doesn’t — protect you from

Email authentication is good at solving a specific problem: impersonation.

When SPF, DKIM, and DMARC are properly aligned and enforced, it becomes much harder for someone else to send email that convincingly claims to be from your domain. That alone removes a huge amount of low-effort abuse and reduces the blast radius of phishing campaigns.

What authentication does not do is decide intent.

A message can be fully authenticated and still be spam. It can pass every check and still be misleading, manipulative, or unwanted. Authentication doesn’t evaluate content, ethics, or usefulness — and it was never meant to.

This distinction matters because email abuse has shifted. Many of today’s scams don’t rely on spoofing at all. They use real domains, legitimate infrastructure, and carefully managed reputations. Authentication helps ensure those domains are accountable, but it can’t tell whether what they’re sending is honest.

Authentication also doesn’t protect recipients once trust has already been established. If someone willingly engages with a sender — signs up, replies, clicks — authentication plays no further role. At that point, the relationship is social, not technical.

Seen clearly, authentication is best understood as a baseline. It establishes who is allowed to speak and whether a message has been altered. Everything beyond that — filtering, blocking, user choice — happens on top.

That baseline is essential. Without it, email would collapse under impersonation. With it, email becomes manageable, even if it remains imperfect.

The mistake is expecting authentication to do more than it was designed to do.

A baseline way to think about sending responsibly

You don’t need to become an email expert to get the basics right. For most senders, the goal isn’t perfection — it’s reducing obvious risk and avoiding self-inflicted problems.

If you own a domain and send email from it, this is the baseline.

Make your sending explicit:

Know which services are allowed to send mail for your domain. If a system isn’t supposed to send, it shouldn’t be listed. Old entries are just as risky as missing ones.

Sign what you send:

Ensure outgoing mail is consistently signed and that keys are maintained. Broken or expired signing quietly undermines trust, even if everything else looks fine.

Align identity with intent:

The domain recipients see should be the domain that’s authenticated. If your visible identity doesn’t match your technical identity, you’re relying on goodwill rather than verification.

Start with visibility before enforcement:

Monitoring comes before blocking. See what’s actually happening before telling the world to reject mail on your behalf. Email ecosystems are rarely as tidy as diagrams suggest.

Pay attention to behaviour, not just setup:

Authentication won’t save careless sending. Sudden volume spikes, poor list hygiene, and ignored engagement signals undo good technical work quickly.

Treat email as a long-term reputation system:

Inbox placement isn’t negotiated per message. It’s earned over time. Small, consistent improvements matter more than one-off fixes.

For individuals running personal domains, the same principles apply — just at smaller scale. You’re still publishing an identity. How carefully you manage it determines how much trust it carries.

The inbox didn’t break — our expectations did

Email still works. Remarkably well, considering its age.

What’s changed isn’t the protocol — it’s the scale, the incentives, and the tolerance for abuse. Email was designed for trusted networks and identifiable senders. Today it’s asked to operate in an environment full of automation, anonymity, and adversarial behaviour.

The reason SPF, DKIM, and DMARC matter isn’t because they “stop spam”. They don’t — at least not directly. They exist to establish accountability. To make it harder to pretend to be someone else. To attach actions to identities over time.

That’s the thread running through everything in this article.

Email is not a fire-and-forget channel. It’s a long-running reputation system where small decisions compound. Domains earn trust slowly and lose it quickly. Senders don’t get infinite retries. Filters don’t care about intent — only patterns.

Once you see email this way, a lot of confusion disappears.

Why “just warming up a domain” doesn’t magically fix deliverability.

Why big providers don’t publish exact rules.

Why the same message lands one day and vanishes the next.

Email isn’t broken. It’s cautious — and for good reason.

And if you treat it like a system that remembers what you do, rather than a pipe you can push messages through, it starts behaving a lot more predictably.

Get the weekly email

A short weekly roundup on email, privacy, and digital trust. No promos. Unsubscribe anytime.