Why Some Marketing Emails Only Offer an Unsubscribe Link

Why many marketing emails force a binary choice — and how unsubscribe-only design mismatches what subscribers actually want.

Most marketing emails end the same way: a small footer link offering one clear option: unsubscribe.

What’s increasingly missing is any way to reduce how often emails are sent, pause messages temporarily, change the type of emails received, or even update the address they’re sent to. The choice is binary: stay on the list, or leave entirely.

At first glance, that seems reasonable. But in practice, it creates a mismatch between what many subscribers want and the options they’re given.

These design choices matter because email remains one of the most personal communication channels people use. How control is handled — or withheld — shapes long-term trust far more than any single campaign.

The shift toward unsubscribe-only emails

A decade ago, preference centres were relatively common. Many mailing lists allowed subscribers to change frequency, opt in to specific categories, or take a temporary break without cutting ties completely.

Today, a growing number of marketing emails offer only a single outcome: unsubscribe from everything.

This isn’t necessarily malicious or careless. In many cases, it’s a deliberate simplification — one link, one action, one clear compliance path. That simplicity, however, comes at a cost: it removes nuance from how people manage their inboxes.

What subscribers usually want instead

For many people, the problem isn’t hearing from a brand at all. It’s hearing from them too often, or about things that are no longer relevant.

Common adjustments subscribers look for include:

- Receiving emails less frequently

- Pausing emails temporarily

- Choosing which categories or campaigns to receive

- Updating the email address on file

When none of those options are available, unsubscribe becomes the only pressure valve — even if it’s not the preferred outcome.

What the data says about unsubscribes

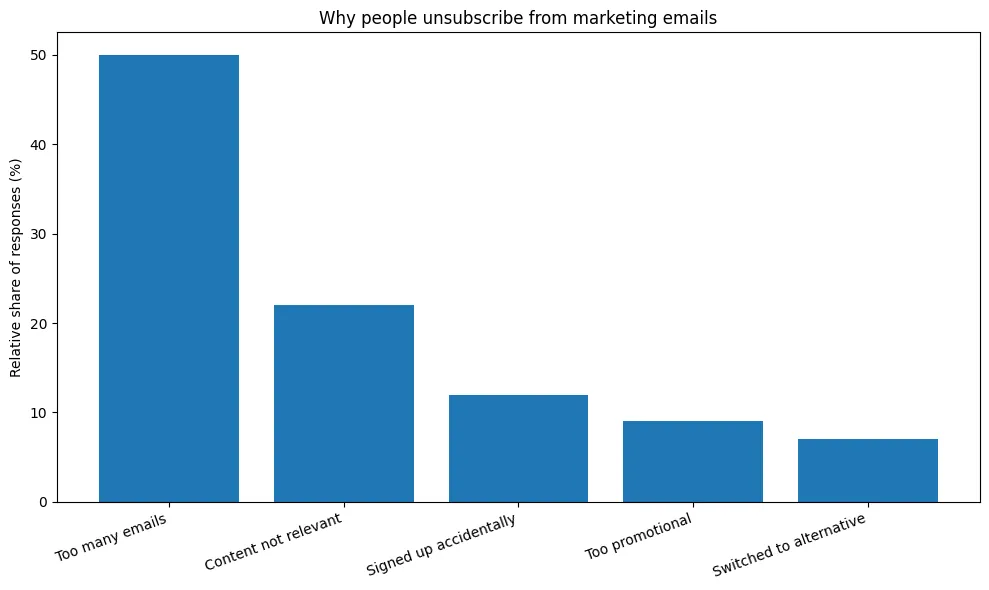

This isn’t just anecdotal. Multiple industry studies point to email frequency as the primary driver of unsubscribes.

Across surveys, “too many emails” consistently ranks as the most common reason people leave marketing lists — ahead of irrelevant content, promotions, or switching to a competitor. In one widely cited study, just over half of respondents said they unsubscribed primarily because emails were sent too frequently.

Tools like DuckDuckGo Email Protection reflect this shift in behaviour. Rather than relying on marketing emails to offer preference controls, users increasingly add their own layer — using forwarding and aliases to limit exposure when flexibility isn’t provided at the source.

A personal example: when unsubscribe becomes the only option

I’ve run into this pattern myself.

After signing up to the Hotel Chocolat mailing list, I started receiving emails almost daily. There was no clear way to reduce the frequency or pause messages — just an unsubscribe link at the bottom of each email.

I didn’t want to stop hearing from the brand altogether. I simply wanted fewer emails. But without any way to adjust that, unsubscribing became the only practical option.

They’re not alone. I’ve had similar experiences with Argos, eBay, Loop Earplugs, and even a small company that custom-made our car mats. In each case, the issue wasn’t relevance — it was volume, and the lack of any middle ground between “everything” and “nothing”.

In practice, that design choice doesn’t reduce email fatigue. It just accelerates list churn.

Why companies design emails this way

From an organisational perspective, unsubscribe-only designs are easy to justify.

They’re simpler to implement, easier to audit, and harder to get wrong from a compliance standpoint. One global unsubscribe action reduces edge cases, avoids conflicting preferences, and produces cleaner lists.

There’s also a cultural factor. Many teams still optimise around volume and engagement metrics, where keeping partially disengaged subscribers on a list can feel like a liability rather than an opportunity.

In that context, a clean unsubscribe can look like good hygiene — even if it masks unmet user needs.

From a compliance perspective, unsubscribe-only designs are easy to justify. UK guidance from the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) makes it clear that recipients must be able to opt out of marketing messages — but it does not require organisations to offer frequency controls or preference centres. For many teams, meeting the minimum requirement becomes the default design choice.

Similar rules apply in the US. The CAN-SPAM requirements enforced by the Federal Trade Commission mandate a clear opt-out mechanism, but allow organisations to offer preference menus as long as users can still unsubscribe from all marketing. Again, preference controls are permitted — just not required.

The unintended consequences for inbox health

Over time, this erodes trust. Brands lose visibility into why people disengage, and subscribers lose confidence that their preferences will be respected.

The result is less meaningful engagement on both sides — not because email stopped working, but because flexibility disappeared.

When people aren’t given ways to adjust how they receive emails, they adapt in other ways. Some ignore messages entirely, while others create rules to auto-archive or filter them. Increasingly, people turn to email forwarding as a way to separate marketing messages from their primary inbox and regain a sense of control.

This kind of inbox adaptation often goes hand in hand with broader efforts to reduce spam and tracking, particularly when marketing emails prioritise volume over relevance. Once trust erodes, subscribers stop engaging — even if they haven’t formally unsubscribed.

Unsubscribe vs preference: a false choice

Unsubscribe links are necessary. They’re legally required and ethically important.

But they don’t have to be the only option.

Good email design treats unsubscribe as a safety exit, not the primary control. Preference settings, frequency adjustments, and pause options allow subscribers to stay engaged on their own terms — often reducing churn in the process.

The choice doesn’t have to be between complexity and compliance. It can be between rigidity and respect.

Some organisations report that offering preference controls — such as frequency or topic selection — can significantly reduce unsubscribe rates, compared with a single unsubscribe-only option.

Some email providers take a different approach by building preference and identity controls directly into the inbox. In my StartMail piece, one of the standout features was the ability to manage aliases and communication patterns without forcing an all-or-nothing decision.

Final thoughts

When marketing emails only offer an unsubscribe link, they assume disengagement is binary. In reality, it’s usually gradual and situational.

Most inbox problems aren’t solved by cutting communication entirely — they’re solved by giving people fewer, better-timed, and more relevant messages.

As inboxes become more tightly managed, the brands that offer control — rather than forcing exits — are likely to be the ones people keep hearing from.

Get the weekly email roundup

I write about email, privacy, and the digital systems that shape trust and identity.

Each week I’ll send a short roundup of what I’ve published (and what I’m thinking about next).

No promos. No drip sequences. Unsubscribe anytime.