DMARC: Deciding What Happens When Email Authentication Fails

DMARC defines what happens when email authentication fails, turning SPF and DKIM results into clear policy decisions that protect domains from spoofing and abuse.

DMARC (Domain-based Message Authentication, Reporting, and Conformance) is often described as “the thing that stops spoofing.”

That’s not quite right.

DMARC doesn’t stop email from being sent. It doesn’t verify messages. And it doesn’t introduce any new authentication checks of its own.

What DMARC does is simpler — and more powerful:

It tells receiving mail servers what to do when SPF or DKIM fail, and whether those results apply to the domain a user actually sees.

DMARC is a policy layer. It turns signals into decisions.

Why SPF and DKIM aren’t enough on their own

By the time DMARC was introduced in the early 2010s, email already had two authentication mechanisms

- SPF could say whether a server was authorised to send

- DKIM could say whether a message had been altered

But neither answered the question inbox providers actually needed to answer:

What should we do when authentication fails — and does it apply to the visible sender?

Without DMARC:

- SPF could pass for one domain while the From address showed another

- DKIM could pass for a signing domain the user had never heard of

- Failures had no consistent consequences

Authentication existed — but enforcement didn’t.

What DMARC actually checks

DMARC doesn’t replace SPF or DKIM. It evaluates their results and adds two critical requirements:

- Alignment

- Policy

Alignment: tying checks to what users see

Alignment is the heart of DMARC.

It answers a deceptively simple question:

Do the domains used by SPF or DKIM match the domain in the visible From address?

If SPF passes but the authorised domain doesn’t align with the From address, DMARC treats it as a failure.

If DKIM passes but the signing domain doesn’t align with the From address, DMARC treats it as a failure.

This is what closes the loophole that SPF and DKIM leave open on their own.

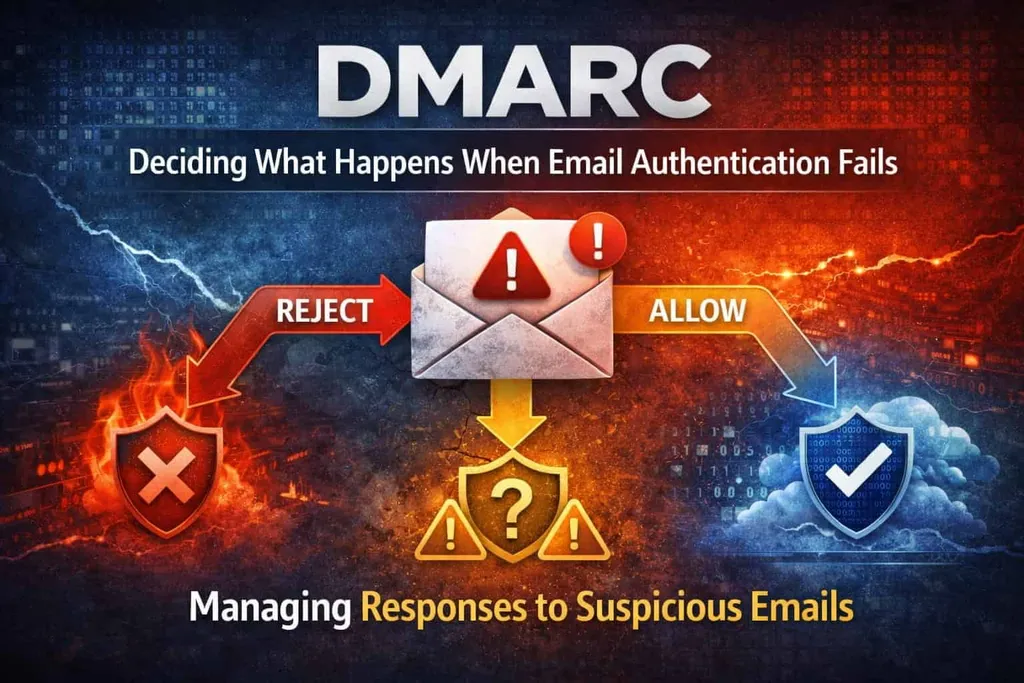

Policy: what to do when checks fail

Once DMARC evaluates alignment, it applies a policy chosen by the domain owner.

That policy is published in DNS and tells receivers what action to take when authentication fails.

The three possible policies are:

- p=none — monitor only

- p=quarantine — treat failures with suspicion

- p=reject — refuse delivery entirely

DMARC doesn’t force a policy. It enforces the one the domain publishes.

A DMARC record example

_dmarc.example.com. IN TXT (

"v=DMARC1; p=quarantine; rua=mailto:[email protected]"

)

Example DMARC TXT record published in DNS, declaring a policy and reporting address

Explained in plain English:

- _dmarc is the fixed DMARC namespace

- p= declares the policy for failures

- rua= tells receivers where to send aggregate reports

- The policy applies to messages claiming to be from this domain in the visible From address

This is what turns authentication from passive signals into enforceable intent.

Why DMARC is the first time “identity” really matters

SPF and DKIM are technical checks.

DMARC is the first layer that explicitly cares about human-visible identity.

It asks:

- Is this message claiming to be from this domain?

- Do the authentication results support that claim?

- If not, what should happen?

That’s why DMARC is where impersonation protection actually begins.

Reporting: the part most people ignore

DMARC doesn’t just enforce policy. It also enables feedback.

When you publish a DMARC record, receiving systems can send reports showing:

- Which sources are sending mail for your domain

- Which messages pass or fail authentication

- How alignment behaves in the real world

These reports are noisy, technical, and hard to read — but they’re how organisations discover:

- Misconfigured services

- Forgotten senders

- Broken DKIM keys

- Forwarding-related failures

Because of that complexity, many organisations rely on third-party services — including offerings from providers like Cloudflare — to collect, aggregate, and interpret DMARC reports at scale.

DMARC isn’t just about blocking mail. It’s about visibility.

Why DMARC is often deployed last

Many domains hesitate to enable DMARC enforcement because it exposes problems upstream.

If SPF or DKIM are brittle — and they often are — DMARC will surface that immediately.

That’s why DMARC is usually rolled out in stages:

- Monitor (p=none)

- Constrain (p=quarantine)

- Enforce (p=reject)

DMARC doesn’t fix authentication. It forces you to confront it.

What DMARC still doesn’t do

Even with DMARC in place, some assumptions remain dangerous.

DMARC does not:

- Judge intent or content

- Guarantee legitimacy

- Prevent all phishing

- Replace reputation or filtering

A message can pass DMARC and still be unwanted, misleading, or abusive.

DMARC answers a narrower question:

Does this message align with the identity it claims, and has the domain owner told us how to handle failures?

That’s powerful — but it’s not absolute trust.

Where DMARC fits in the system

Taken together:

- SPF says who is allowed to send

- DKIM says whether the message was altered

- DMARC says whether those results apply — and what to do if they don’t

DMARC is the decision layer that makes SPF and DKIM matter.

Without it, authentication exists but enforcement is optional.

With it, domains finally get a say in how their identity is protected.

Understanding DMARC means understanding responsibility

DMARC doesn’t protect email by itself. It makes responsibility explicit.

It lets domain owners say:

If mail claiming to be from us can’t prove it — don’t accept it.

DMARC only makes sense when viewed alongside the mechanisms it depends on. If you want the full picture — how SPF, DKIM, and DMARC interact, where each one stops, and why none of them work in isolation — the overview post explains how email authentication actually works.

That single shift is why DMARC changed email more than any individual authentication check before it.

For the formal specification of DMARC, including policy, alignment, and reporting rules, see the official documentation at dmarc.org.

Get the weekly email

A short weekly roundup on email, privacy, and digital trust. No promos. Unsubscribe anytime.